By Kerri Barile

One of the most exciting finds on an archaeological site are the remains of a building or structure—evidence of people modifying their natural world to create a controlled space. Whether it is a dwelling, store, barn, or other building, the activity of using tools to create construction materials and combining these fragments to craft shelter is one of the hallmarks of humanity. During the Riverfront Park data recovery in Fredericksburg, Virginia, Dovetail Cultural Resource Group found not one but five foundations, each a unique symbol of the city’s evolution (Photo 1). The archaeological work was done at the request of the City of Fredericksburg prior to park development. This blog is the first of several that will focus on the results of our January/February 2019 data recovery at the Riverfront Park. We thought we would set the scene for upcoming installments by discussing the buildings that once dotted the landscape. Future blogs will take the next step and describe the thousands of artifacts once used by area inhabitants and recovered during this incredible dig.

The first European settlement on the Fredericksburg riverfront occurred early in the community’s history. Even before the town had a formal street system, dwellings were being erected along the riverbanks. One of the earliest was a home that we now call the Rowe-Goolrick House, located at the southern end of the proposed park. Built in the mid-eighteenth century, this two-story, three-bay home did not face today’s street grid but rather the original town ferry lane, which ceased use shortly after the home was constructed. The foundation of the house was fashioned of local Aquia sandstone, forming a basement and support system for the frame structure above. The home was demolished in 1973 to make way for a parking lot. During the Riverfront data recovery, Dovetail uncovered the northeast corner of the foundation, still in pristine condition (Photo 2). Possible original support posts were even found in place in the basement fill. Dendrochronology (tree ring dating) is being done on these supports to date these incredible building fragments.

Photo 2: The Rowe-Goolrick House in 1933 (left) (Library of Congress 1933) and the Home’s Stone Foundation (right), Found under a Parking Lot.

On the opposite side of the park, in the northern segment near Hanover Street, the team uncovered not one but two incredible foundations. Each featured handmade brick with sand temper made in wooden molds; the foundations were fastened with mud mortar. In the northwest corner was the foundation of a one-story, four-bay brick duplex at 717–719 Sophia Street built around 1780. Interestingly, this home had a central chimney that serviced both sides of the double dwelling—a feature usually seen in New England (Photo 3). In the northeast corner was the brick foundation of the circa 1832 Ferneyhough ice house, a public ice facility. This feature measured over 30 feet in length, dug into a subsoil of very dense clay (so dense that the backhoe could not penetrate the soils) (Photo 4). Excavation of this clay with hand tools to adequately lay the deep foundation would have been incredibly challenging!

Photo 3: Brick Duplex at 717–719 Sophia Street in 1927 (left) (Library of Congress 1927) and the Building’s Foundation and Central Chimney Base Uncovered During the Dig (right).

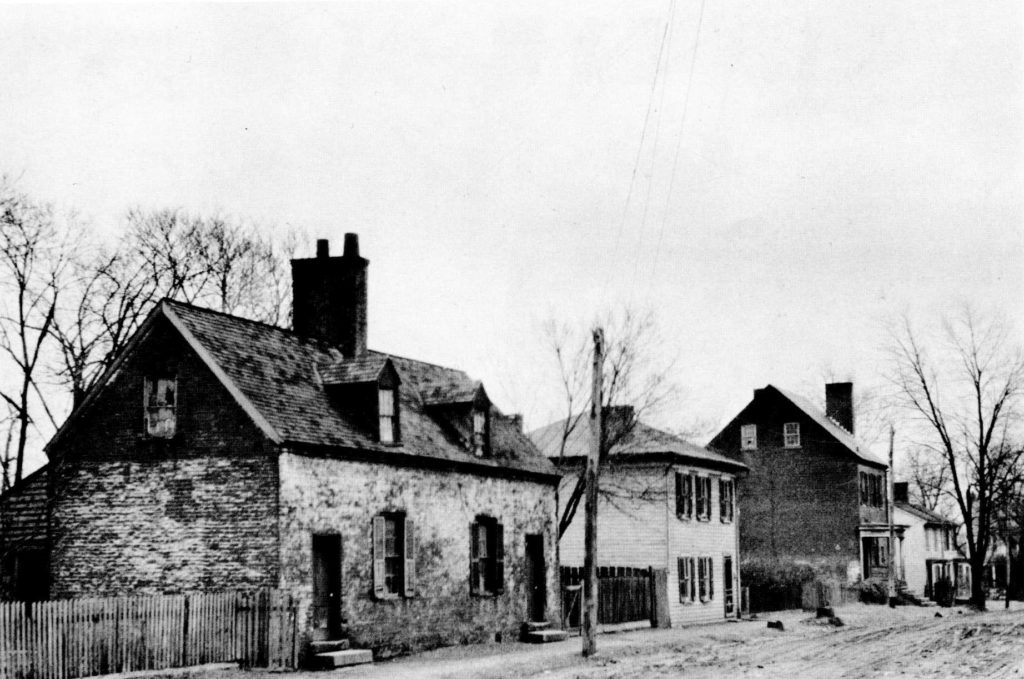

In the middle of the park, archaeologists found the brick foundation of a postbellum home once located at 713 Sophia Street and an antebellum duplex that once stood at 701–703 Sophia Street (Photo 5). Both of these buildings had a timber-frame structural system sitting on brick, stone, and wooden pier foundations. Each was in use for only 50 to 75 years before they were demolished, reflecting the transitory nature of life along the river where repeated flooding and changing transportation needs rendered an ever-changing landscape. All of the buildings found in the park area were someone’s home, someone’s work, someone’s life. When joined, these fragments come together to tell the story of so many who once walked in our footsteps and dwelled at our doors.

Photo 5: The Fredericksburg Riverfront Park Around 1920. From left to right: brick duplex at 717–719 Sophia Street; home at 713 Sophia Street; Home at 705 Sophia Street (not excavated during current fieldwork); and wood duplex at 701–703 Sophia Street (Shibley 1976:137).

References:

Library of Congress

1927 Cabin, Water Street, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Frances Benjamin Johnson Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008675923/, accessed July 2013.

1933 House, 607 Sophia Street, Fredericksburg, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Historic American Building Survey. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/va0925.photos.165656p/, accessed July 2013.

Shibley, Ronald E.

1976 Historic Fredericksburg: A Pictorial History. The Donning Company/Publishers, Inc., Norfolk, Virginia.

Any distributions of blog content, including text or images, should reference this blog in full citation. Data contained herein is the property of Dovetail Cultural Resource Group and its affiliates.